1. California awaits "The Big One"

California is known all over the world for its size, its sun, and its surf, its glamour and its optimism. But it is known too as "Earthquake Country " — a truly vulnerable region where big devastating quakes have occurred in the past and could happen again. It is unlikely that a disaster on the scale of recent disasters in Italy or Japan could occur in California; California has learnt from its past disasters, and most buildings are designed to withstand major quakes. Nevertheless, Californians are worried. When will the next big quake strike the state, and where will all the shaking and crumbling and rocking begin?

Nobody knows for sure, but at all times California is on the alert. The earth is permanently monitored with high-tech seismographs situated in universities and government research stations; they are constantly watched by highly-trained employees and volunteers from the California Office of Emergency Services; and students in every school receive training in what to do in the event of an earthquake.

Working at Menlo Park, near Stanford University, in the middle of "Earthquake Country", scientists from the United States Geological Survey are always monitoring and studying fault systems, and trying to predict where earthquakes are going to take place next.

Back in 1988, a team of USGS scientists completed a ten-year survey on "earthquake possibilities", and came up with the conclusion that there's going to be a lot of shaking in the years ahead. In particular, they predicted a 50% possibility of an exceptionally big quake of 8.3 sometime before 2018, somewhere along the San Andreas or Hayward faults.

In the two centuries from 1812 to 2012 , California has suffered dozens of earthquakes. The last seriously damaging earthquake was the 1994 quake in the Los Angeles area, that registered 6.7 on the Richter scale, and did up to $40 billion worth of damage. A much stronger quake, of 7.2 on the Richter scale, struck Baja California (Mexico) in 2010, doing over a billion dollars worth of damage in this far less populated area.

This highway bridge near San Francisco collapsed in a 1989 earthquake

Since 1812, California has experienced 15 major earthquakes of a magnitude of 7.0 or larger. Two of these were the great quake of 1857, with an estimated magnitude of 8.3, and the great earth-quake of 1906, which nearly levelled the port city of San Francisco and had a magnitude of 8.25.

Responsibility for California's earthquakes lies in the fact that the state sits atop the famous and terrifying San Andreas Fault. This fault rocks and quakes often and unexpectedly as the earth's tectonic plates shift along fault lines that run 700 miles from the Mexican border to the north California coast. It is almost unbelievable that more than 20 million people should choose to live along this fault; but because their state has prosperity, an ideal climate, and a wonderful ambiance, Californians take a laissez-faire attitude to the potential danger.

Living in the hills above the Hayward Fault, I know all about the danger. Like many Californians, I buy costly earthquake insurance for my home. If I walk along certain streets in the town of Hayward, I can see how the earth creeps and shifts. In some places, the town looks as if the architects and builders made big mistakes in construction, because the buildings are out of kilter.

Actually, what has happened is that the streets have cracked and shifted, so that curbs no longer meet. Houses have shifted, so that walls are uneven. Buildings have interior and exterior cracks that can't be prevented, because the slowly shifting earth causes an inexorable movement in foundations, walls and streets! Geologists believe that displacements along this fault have been occurring for 15-20 million years. The drift can be measured — in the present decades — as a displacement of two inches per year, on average. It doesn't take an expert to figure out what moving part of a building two inches a year will do to that structure. During the destructive 1906 earthquake, in some places the earth moved as much as 21 feet!

Scientists now know that major earthquakes occur at about 150-year intervals along the San Andreas fault; but in the future, they will probably not happen unannounced. Scientists can now better predict when a quake is coming, by foreshocks and other techniques discovered in the studies they are constantly undertaking, so Californians can normally fo to bed at night without worrying whether the house will fall down around them while they are sleeping.

Still, with or without a warning, the next Big One, when it comes, will still do enormous damage. It's something that we Californians just live with

2.The story of the skyscraper

If you ask a person to describe an American city, the chances are that he will mention the word skyscraper. Tall buildings, their tips sometimes hidden in the clouds, have become the symbol of the American metropolis, a symbol of twenty-first century urban civilisation. American cities have not always had skyscrapers, but it is now almost a century and a half since the first skyscrapers began to distinguish their skylines.

For millions of people coming to America from Europe, the first proof that they had reached a new world was the moment when they first caught sight of the skyline of Manhattan. Surrealistic, superhuman, the skyline was like nothing they had ever seen in the old world — a concentration of tall buildings, their tops scraping the sky, hundreds of feet above the ground. These were New York's famous skyscrapers! This was America!

The Home Insurance building, Chicago: 1884

The first skyscrapers, however, did not develop in New York, but in Chicago, in the late nineteenth century. Chicago at that time was the boom town of the United States — New York was just the front door. Chicago was at the centre of the new American adventure, and the new adventure was the West. Chicago was the point at which the West began.

In the year 1871, a large part of booming Chicago was destroyed as a major fire engulfed much of the downtown area. The fire, however, was a great stimulus to architects: not only did it show them the need to design modern buildings that would not be liable to burn very rapidly, but it also gave them plenty of opportunities to put their new theories into practice.

By the late 1800's architects and engineers had made great steps forwards. Until the nineteenth century, the height of buildings had been limited to a maximum of about ten stories as a result of the building materials used — wood, brick or stone. With the exception of churches and cathedrals, few earlier buildings went higher than this, because they could not do so. And even the great churches of mediaeval Europe had to respect basic mechanical constraints. The walls needed to be terribly thick at the bottom, and often supported by complicated systems of buttresses and flying buttresses, to stop them falling down.

In the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution resulted in the development of new techniques, notably the use of iron. This allowed the building of much bigger buildings, in particular railway stations, the "cathedrals of the Industrial Revolution", and exhibition buildings. Opened in 1889, the nineteenth century's most famous iron and steel structure reached unheard-of new heights. The Eiffel Tower, 1010 feet high, pointed the way to the future: upwards!

Yet plain iron and steel structures had their limitations. They were not really suitable for the design of human habitations or offices — and in the event of fire, they could collapse very rapidly.

It was in fact the combination of the old and the new that allowed the development of the skyscraper: the combination of metal frames and masonry cladding. The metal frame allowed much greater strength and height, without the enormous mass and weight of stone-built structures; the masonry cladding allowed traditional features, such as rooms and partitions, to be included in the design with relatively few problems. The man generally considered as the father of this new technique was the Chicago architect William Jenney.

Though Jenney was the father of the metal-frame building, his own buildings did not go any higher than contemporary brick or stone buildings already going up in Chicago, New York, and elsewhere. Jenney's "Home Insurance Building" in Chicago (photo above) was only ten stories high, and stylistically similar to other buildings which did not use a metal frame.

It was left to Jenney's successors, notably Lewis Sullivan and David Burnham, working in Chicago and New York, to go futher. Burnham's "Flat-iron Building" in New York, erected in 1902, reached new heights for an office building, with 20 stories; and at 290 feet (about 90 metres), it is known as New York's first skyscraper.

The reasons for building skyscrapers were clear, particularly in a city like New York, whose downtown district, Manhattan, could not expand very easily on a horizontal plane, limited as it was by the Hudson and East rivers. Apart from upwards, there were not many directions in which Manhattan could grow. And once the building techniques had been mastered, vertical expansion became the most desirable solution for the city's businessmen.

Since those early days, and in particular since the Second World War, skyscrapers have mushroomed in all the world's big cities; and they keep getting higher and higher. Before the First World War, New York's "Woolworth Building" had reached 792 feet (241 metres) ; and by the Second World War, the Empire State Building —for many years the world's tallest — had actually passed the Eiffel Tower. In the 1970s, the enormous twin towers of the World Trade Center, 107 stories high, went even further. But did they go too far? As bold icons of modern America, they became the target of terrorism when radical Islamic terrorists used passenger jets to destroy them, in the terrible events of 9/11 - the 11th of September 2001.

Architectural dreamers of a hundred years ago or more imagined cities in the sky, giant buildings where people lived thousands of feet above the ground, above the clouds, above the pollution. Today, although some people believe that modern skyscrapers are too high, they now characterise cities all over the world; and they keep getting higher. Fires in a few tall buildings, for instance in Dubai, have led to further questions being asked; but in spite of the occasional disaster, skyscrapers are here to stay — at least for offices and city hotels. Symbols of our civilisation, they are not likely to be replaced.

3.Wall Street Culture - the heart of America

For Americans, the most important street in the USA is Wall Street

The New York Stock Exchange, on Wall Street.

The New York Stock Exchange, on Wall Street.

Say "the streets of New York" to a non-American, and he'll probably think of Times Square, Madison Avenue or Broadway; but mention the subject to an American and for many the first name that comes to mind will be Wall Street.

For many, Wall Street is indeed just "the street", probably the most important street in the USA or even in the world; for what goes on on Wall Street, more perhaps than what goes on in Congress, can have a direct influence on the lives of everyone in the USA, if not most people in the world.

Wall Street is of course the home of theNew York Stock Exchange, the financial heart of the American business world. Each day, billions of dollars of shares are traded on the floor of the stock exchange on behalf of companies, pension funds and private individuals wanting to protect their investments or their life's savings, and make sure that they too are on the bandwaggon of prosperity.

For many, Wall Street is indeed just "the street", probably the most important street in the USA or even in the world; for what goes on on Wall Street, more perhaps than what goes on in Congress, can have a direct influence on the lives of everyone in the USA, if not most people in the world.

Wall Street is of course the home of theNew York Stock Exchange, the financial heart of the American business world. Each day, billions of dollars of shares are traded on the floor of the stock exchange on behalf of companies, pension funds and private individuals wanting to protect their investments or their life's savings, and make sure that they too are on the bandwaggon of prosperity.

Wall Street's ups and downs affect the lives of most Americans

Wall Street's ups and downs affect the lives of most Americans

The New York Stock Exchange is the biggest and most active stock exchange in the world; over half of all adult Americans have some, if not all, of their savings invested directly on Wall Street, so it is not surprising that the fluctuations of the Street's famous indexes, the Dow Jones and the Nasdaq, are followed daily by millions of ordinary Americans. When the Dow and the Nasdaq are on a rise, millions of Americans feel more prosperous; when they are falling, millions start feeling worried about their financial security and their retirement years. Yet more importantly, when Wall Street booms it is a sign that the American economy is booming, creating jobs and prosperity for people throughout the nation; when Wall Street slumps for more than a short period, it is because the American economy is slowing down, putting investment and jobs at risk.

Nevertheless, in spite of its periodic crashes and downturns, most Americans know very well that by investing directly in the stock market, they are probably ensuring the best possible long term return on their investments.

Over time, direct investments on Wall Street have always done better than most other forms of long-term placement, and logically speaking this is inevitable. Ultimately, most forms of investment depend on the performance of the US economy in general, and by investing directly on Wall Street, American investors are simply ensuring that they personally take full advantage of the growth of the stock market, rather than share their gains with banks, investment trusts or other intermediaries offering investment services.

Nevertheless, in spite of its periodic crashes and downturns, most Americans know very well that by investing directly in the stock market, they are probably ensuring the best possible long term return on their investments.

Over time, direct investments on Wall Street have always done better than most other forms of long-term placement, and logically speaking this is inevitable. Ultimately, most forms of investment depend on the performance of the US economy in general, and by investing directly on Wall Street, American investors are simply ensuring that they personally take full advantage of the growth of the stock market, rather than share their gains with banks, investment trusts or other intermediaries offering investment services.

CRASHES ON THE STREET

The risk of a crash on Wall Street is a reality that must always be borne in mind: Wall Street "crashed" most spectacularly in the fall of 1929, when share values dropped over 50% in the space of a few days. By the time the fall bottomed out in 1932, over 80% had been "wiped off" the value of shares on the American stock market, and the Great Depression had begun.

Before 1929, as the stock market boomed, over a million Americans had been speculating on the Street, borrowing money that they did not have in order to buy shares for sale at a profit. When the crash came, hundreds of thousands of these speculators, both individuals and companies, went bankrupt, causing immense distress and poverty.

More recently, Wall Street crashed in 2007 - 2008, almost triggering a collapse of the world financial system. When the stock market eventually stopped falling in March 2009, it had lost 54% of its value, and many people had lost their life's savings.

Previously in 1997, almost over a third of its value was wiped out in a few days; but this time the consequences were less dramatic. While most Americans saw the value of their savings tumble, few went bankrupt as a result.

Before 1929, as the stock market boomed, over a million Americans had been speculating on the Street, borrowing money that they did not have in order to buy shares for sale at a profit. When the crash came, hundreds of thousands of these speculators, both individuals and companies, went bankrupt, causing immense distress and poverty.

More recently, Wall Street crashed in 2007 - 2008, almost triggering a collapse of the world financial system. When the stock market eventually stopped falling in March 2009, it had lost 54% of its value, and many people had lost their life's savings.

Previously in 1997, almost over a third of its value was wiped out in a few days; but this time the consequences were less dramatic. While most Americans saw the value of their savings tumble, few went bankrupt as a result.

In today's America, borrowing money solely for the purpose of speculating on Wall Street is not a common habit, so the money that was "lost" in recent crashes was mostly money that people owned themselves, not money that they owed to someone else.

One day no doubt, in some unforeseen future, Wall Street will crash spectacularly again; but when that happens there will have to be both a cause and an effect. The most likely cause will be a major world crisis; the most likely effect, given today's "global economy", will be a major economic catastrophe around the world, perhaps similar to the hyperinflation that affected Germany under the Weimar republic.

If that happens, society as we know it will grind to a halt, and most forms of saving, except perhaps gold and real estate, will lose most of their value; until that day, Wall Street will remain as one of the nerve centers of the global economy.

One day no doubt, in some unforeseen future, Wall Street will crash spectacularly again; but when that happens there will have to be both a cause and an effect. The most likely cause will be a major world crisis; the most likely effect, given today's "global economy", will be a major economic catastrophe around the world, perhaps similar to the hyperinflation that affected Germany under the Weimar republic.

If that happens, society as we know it will grind to a halt, and most forms of saving, except perhaps gold and real estate, will lose most of their value; until that day, Wall Street will remain as one of the nerve centers of the global economy.

4.The story of Ellis Island

Mass migrations have marked the history of the human race ever since people began to dream of a better life

Migration is in the news in 2017, as Donald Trump tries to set up new physical and administrative barriers against people wanting to enter the USA - mostly from Central America, Asia and Africa. But a century ago, it was people in Europe who were migrating in mass, looking for a better life in the USA. Ellis Island, the small island in New York Harbor was, for millions of would-be immigrants, their first experience of the promised land.

The year is 1906, the date November 16th. Franz and Ulrike Schumacher and their three children have just disembarked from the Hamburg-Amerika line steamship that has carried them across the stormy North Atlantic Ocean from Germany.

The year is 1906, the date November 16th. Franz and Ulrike Schumacher and their three children have just disembarked from the Hamburg-Amerika line steamship that has carried them across the stormy North Atlantic Ocean from Germany.

Like the thousands of other people milling around them, they are totally bewildered, caught up in a mixture of hope and apprehension, as they crowd into a vast waiting room. The room sounds like the Tower of Babel, for few of those in it speak a word of English. They speak German, Polish, Dutch, Hungarian, or Russian maybe, yet they have come, seeking a new life in a new world; and now they are on American soil for the first time. This is America! America! Or at least it is Ellis Island.

After interminable hours of waiting, the Schumacher family are finally called to a desk; immigration officials study their papers, and ask them where they intend to go. They don't ask how long they're planning to stay, however, since they know the answer already. All those who pass through Ellis Island -- and that could mean over 11,000 people per day -- are would-be immigrants. They are looking to start a new life in a new world.

For many, passing through Ellis Island was not so much a matter of stepping into a new world, it was stepping into a new life, a new character. And so it was that the man who finally led his family through the door and onto the ferry packed with a jostling crowd of new Americans was not Franz Schumacher any more, but Frank Shoemaker, even if he still didn't understand more than a couple of words of English.

The year is 1906, the date November 16th. Franz and Ulrike Schumacher and their three children have just disembarked from the Hamburg-Amerika line steamship that has carried them across the stormy North Atlantic Ocean from Germany.

The year is 1906, the date November 16th. Franz and Ulrike Schumacher and their three children have just disembarked from the Hamburg-Amerika line steamship that has carried them across the stormy North Atlantic Ocean from Germany.Like the thousands of other people milling around them, they are totally bewildered, caught up in a mixture of hope and apprehension, as they crowd into a vast waiting room. The room sounds like the Tower of Babel, for few of those in it speak a word of English. They speak German, Polish, Dutch, Hungarian, or Russian maybe, yet they have come, seeking a new life in a new world; and now they are on American soil for the first time. This is America! America! Or at least it is Ellis Island.

After interminable hours of waiting, the Schumacher family are finally called to a desk; immigration officials study their papers, and ask them where they intend to go. They don't ask how long they're planning to stay, however, since they know the answer already. All those who pass through Ellis Island -- and that could mean over 11,000 people per day -- are would-be immigrants. They are looking to start a new life in a new world.

For many, passing through Ellis Island was not so much a matter of stepping into a new world, it was stepping into a new life, a new character. And so it was that the man who finally led his family through the door and onto the ferry packed with a jostling crowd of new Americans was not Franz Schumacher any more, but Frank Shoemaker, even if he still didn't understand more than a couple of words of English.

* * *

Ever since the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the United States has been a nation of immigrants. While today the pattern of immigration is not what it used to be (most immigrants coming from Latin America or Asia) and immigration policies are now designed to restrict entrance to the USA, things were very different in the early part of the twentieth century.

Ellis Island, almost in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty at the entrance to New York Harbor, was the first stop on American soil for some twelve million immigrants between the years 1892 and 1954. For most, it was "a portal of hope and freedom"; for just a few, it was the "Island of Tears", when they were turned away for failing to meet the various immigration laws and requirements.

During its years of operation, Ellis Island was the principal port of immigration into the United States, processing approximately 75% of all the immigrants into America over the period.

The original three acre island got its name from a previous owner, Samuel Ellis. At the end of the eighteenth century, the State of New York secured the island in order to build fortifications as part of its harbor defense system.

It was in 1890 that that Congress set aside funds to begin improvements on the island, so that a federal immigration station could be built to replace the existing facilities at Castle Garden, in lower Manhattan.

The original island was expanded to several times its size, and the new immigration station opened on January 1st, 1892. Five years later, it was destroyed by fire; but it was soon rebuilt, with an impressive French Renaissance style brick building, which opened for business on December 17th 1900 and processed 2,251 immigrants that very same day. The part of the building whose image remained most clearly marked in the memories of those who passed through, was the vast registry room occupying the whole central section of the second floor; it was here that most of the processing of would-be immigrants took place.

During the next half century, the small island grew to its present size, as it was joined by landfill to three adjacent islands. The main building was supplemented with a power house, kitchens, a hospital and contagious diseases wards, a dormitory building, a bakery and several other structures.

In the early 1920's, though, immigration declined sharply, as restrictive immigration laws were passed. These put an annual ceiling on immigration, and established quotas for each foreign nation. They also made it compulsory for would-be immigrants to fill in papers at the US consulate in their country of origin, rather than on arrival. Thereafter, only those whose papers were not in order, or who needed medical treatment, were sent to Ellis Island.

The facilities were increasingly used for the assembly and deportation of aliens who had entered the USA illegally, or of immigrants who had violated the terms of their admittance. And finally, on November 12th 1954, the Ellis Island immigration station ceased operation.

Now it is open again, but as a museum, to tell the story of a fundamental stage in the making of modern America. The story needs to be told; what better place to tell it than on Ellis Island ?

5.Thanksgiving

- a very American festival

Thanksgiving is perhaps the most American of America's festivals. While many countries have days when everyone eats a lot, only the Americans have a day on which they celebrate having enough to eat. Perhaps this may seem rather superfluous in a country whose inhabitants are today among the best-fed in the world; but to Americans, Thanksgiving is a reminder that this was not always the case.

The First Thanksgiving in 1621 - from a painting by JLG Ferris

The last weeks of the year are a festive time in most countries; but while Europeans just celebrate Christmas and the New Year, Americans begin their festive season about a month earlier. The feast of Thanksgiving, celebrated on the fourth Thursday in November, is second only in importance to Christmas in the American calendar of feast days.

Thanksgiving is the oldest non-Indian tradition in the United States, and was first celebrated in the year 1621. It was in this year that the men and women in Plymouth, one of the first New England colonies, decided to establish a feast day to mark the end of the farming year.

As devout Protestants, they called their feast day "Thanksgiving", a day on which people could celebrate and give thanks to God for the crops that they had managed to grow and harvest. This was not in fact an original idea, but was based on the English "Harvest Festival", an old customwhereby people gave thanks to God once the crops were all in.

In America however, a successful harvest was more significant than in England, for any failureto bring in an adequate supply of crops could be fatal for a new colony, struggling to set itself up in an alien continent. Several early North Americans colonies failed because the colonists were killed off by disease or fighting, and others perished because they did not have time to prepare enough land and grow enough food for their needs during the long cold winter months. The year 1621 was a particularly bountiful one for the Plymouth colonists, so they "gave thanks" for their good fortunes.

In the years that followed, other colonies introduced their own Thanksgiving festivals, each one at first choosing its own date, and many varying the date according to the state of the harvests. In 1789, President George Washington gave an official Thanksgiving Day address in honor of the new Constitution; and Thanksgiving Day, like Independence Day (July 4th) became one of America's great days.

Nevertheless, at first the date was not fixed nationally; indeed, it was not until 1863 that President Abraham Lincoln declared that Thanksgiving Day should be celebrated on the last Thursday of November. Other presidents made similar proclamations, and the date of Thanksgiving tended to move around until the year 1941, when Congress and the President jointly declared that it should henceforth be fixed on the fourth Thursday of November. Since then, Thanksgiving Day has remained fixed.

Thanksgiving is the oldest non-Indian tradition in the United States, and was first celebrated in the year 1621. It was in this year that the men and women in Plymouth, one of the first New England colonies, decided to establish a feast day to mark the end of the farming year.

As devout Protestants, they called their feast day "Thanksgiving", a day on which people could celebrate and give thanks to God for the crops that they had managed to grow and harvest. This was not in fact an original idea, but was based on the English "Harvest Festival", an old customwhereby people gave thanks to God once the crops were all in.

In America however, a successful harvest was more significant than in England, for any failureto bring in an adequate supply of crops could be fatal for a new colony, struggling to set itself up in an alien continent. Several early North Americans colonies failed because the colonists were killed off by disease or fighting, and others perished because they did not have time to prepare enough land and grow enough food for their needs during the long cold winter months. The year 1621 was a particularly bountiful one for the Plymouth colonists, so they "gave thanks" for their good fortunes.

In the years that followed, other colonies introduced their own Thanksgiving festivals, each one at first choosing its own date, and many varying the date according to the state of the harvests. In 1789, President George Washington gave an official Thanksgiving Day address in honor of the new Constitution; and Thanksgiving Day, like Independence Day (July 4th) became one of America's great days.

Nevertheless, at first the date was not fixed nationally; indeed, it was not until 1863 that President Abraham Lincoln declared that Thanksgiving Day should be celebrated on the last Thursday of November. Other presidents made similar proclamations, and the date of Thanksgiving tended to move around until the year 1941, when Congress and the President jointly declared that it should henceforth be fixed on the fourth Thursday of November. Since then, Thanksgiving Day has remained fixed.

THANKSGIVING RITES

Once a communal festival, where whole communities celebrated together, Thanksgiving is today the great family festival; but apart from that, it has not changed greatly.

The heart of Thanksgiving is still the fruit of the land; and the Thanksgiving feast is based, essentially, on the native American foods that allowed the early settlers to survive: turkey, corn, potatoes and squash.

The wild turkeys, large birds that lived in the forests of North America, were like a miracle for the early colonists who could trap them with ease; and turkey has always been the centerpiece of the Thanksgiving feast.

Potatoes were unknown to Europeans before the discovery of North America, and it was Indians who taught the early colonists how to grow them and eat them.

Maize, the great native North American cereal, is another ingredient of the Thanksgiving meal, eaten in the form of sweet corn.

Finally, for dessert, no Thanksgiving meal is complete without "pumpkin pie", the traditional tart made from pumpkins, enormous round orange types of squash.

The heart of Thanksgiving is still the fruit of the land; and the Thanksgiving feast is based, essentially, on the native American foods that allowed the early settlers to survive: turkey, corn, potatoes and squash.

The wild turkeys, large birds that lived in the forests of North America, were like a miracle for the early colonists who could trap them with ease; and turkey has always been the centerpiece of the Thanksgiving feast.

Potatoes were unknown to Europeans before the discovery of North America, and it was Indians who taught the early colonists how to grow them and eat them.

Maize, the great native North American cereal, is another ingredient of the Thanksgiving meal, eaten in the form of sweet corn.

Finally, for dessert, no Thanksgiving meal is complete without "pumpkin pie", the traditional tart made from pumpkins, enormous round orange types of squash.

6.Mardi Gras

in New Orleans

New Orleans, the great city at the mouth of the Mississippi is one of the most colorful, most cosmopolitan and most European of American cities.

Though very few people in the city now speak or understand much French, New Orleans prides itself on its French heritage. The historic center of the city is known as the French Quarter, and the city is famous across the United States for its restaurants and its "Mardi Gras" celebrations.

It is still one of America's great ports, where goods that have traveled down the Mississippi valley by barge or by truck or by train are offloaded and trans-shipped, to be exported all over the world.

Though very few people in the city now speak or understand much French, New Orleans prides itself on its French heritage. The historic center of the city is known as the French Quarter, and the city is famous across the United States for its restaurants and its "Mardi Gras" celebrations.

It is still one of America's great ports, where goods that have traveled down the Mississippi valley by barge or by truck or by train are offloaded and trans-shipped, to be exported all over the world.

Mardi Gras parade in New Orleans

By John Robillard

Mardi Gras, meaning literally "Fat Tuesday" was first celebrated in Louisiana by French colonists in the eighteenth century. It was, in those days, a day of feasting before the start of Lent, the 40-day period leading up to Easter.

As the last "normal" day before the austerity of Lent, "fat Tuesday" was a day to make the most of, a day of carnivals, eating, drinking and revelry. It has remained a day of carnival ever since; but the original French celebrations are just a small part of today's festivities. Mardi Gras, New Orleans style, owes as much to Afro-Caribbean customs and the Latin American carnival tradition as it does to the French colonists who established it in their new city.

The Mardi Gras celebrations actually last for several weeks. About a month before the main carnival, a season of elaborate balls and parties begins: the official Mardi Gras program is published, and shops start selling the very sweet and colorful "King Cake", a delicacy that can only be found during this holiday season.

In other parts of Louisiana, the first Mardi Gras parades actually take place three to four weeks before the big carnival in New Orleans, and even in the city itself, smaller parades begin two weeks before the big day.

My first Mardi Gras party took place in a friend's apartment in New Orleans a few days before the parade. The apartment was decorated out in the season's traditional colors of green, gold and purple; the hi-fi system pounded out carnival music, while the guests danced, talked, and ate King Cake, washed down with "Blackened Voodoo Beer", another specialty brewed in a local brewery.

On Fat Tuesday itself, I joined the hundreds of thousands of local people and visitors, to watch the processions wind their way through the streets of New Orleans. The processions are organized by groups called "Krewes", which each have mythological or historic names, such as Proteus, Endemion, or Bacchus. The one I liked best was Zulu, a parade organized by members of the city's black community, resplendent with its colorful ornate floats and costumes based on African themes.

Perhaps the most astonishing aspect of Zulu and other parades was the "throws". As the floats move slowly through the crowds, tradition has it that those on them should throw all kinds of trinketsinto the crowd — plastic necklaces, engraved plastic cups, plastic medallions (a coveted prize) and other souvenirs. Most parade-goers do all they can to catch these materially worthless items, and I found myself quickly caught up in the frenzy, scraping on the sidewalk among the surging spectators to proudly pick up my plastic prize. In the heat of the moment, it's hard not to be caught up in the madness of this ritual, in spite of the worthlessness of the prizes!

Traditionally, people in New Orleans use the "throw cups" they pick up, and decorate their cars or homes with the other souvenirs they take home.

As a Yankee spending my first Mardi Gras in New Orleans, however, I made some mistakes in planning my time. There is so much going on at Carnival time, that you can't see everything, and I was disappointed not to see more of the city's famous Dixieland jazz bands parading through the streets, but obviously I was often in the wrong place at the wrong time.

After a year, I know that I still have a lot to learn about the customs, cultures and traditions of Mardi Gras in New Orleans. This year, I'll try and restrain myself during the throws, so that I won't come home with a bagful of plastic objects that I simply have to recycle. I'll let someone else have that pleasure!

Mardi Gras, meaning literally "Fat Tuesday" was first celebrated in Louisiana by French colonists in the eighteenth century. It was, in those days, a day of feasting before the start of Lent, the 40-day period leading up to Easter.

As the last "normal" day before the austerity of Lent, "fat Tuesday" was a day to make the most of, a day of carnivals, eating, drinking and revelry. It has remained a day of carnival ever since; but the original French celebrations are just a small part of today's festivities. Mardi Gras, New Orleans style, owes as much to Afro-Caribbean customs and the Latin American carnival tradition as it does to the French colonists who established it in their new city.

The Mardi Gras celebrations actually last for several weeks. About a month before the main carnival, a season of elaborate balls and parties begins: the official Mardi Gras program is published, and shops start selling the very sweet and colorful "King Cake", a delicacy that can only be found during this holiday season.

In other parts of Louisiana, the first Mardi Gras parades actually take place three to four weeks before the big carnival in New Orleans, and even in the city itself, smaller parades begin two weeks before the big day.

My first Mardi Gras party took place in a friend's apartment in New Orleans a few days before the parade. The apartment was decorated out in the season's traditional colors of green, gold and purple; the hi-fi system pounded out carnival music, while the guests danced, talked, and ate King Cake, washed down with "Blackened Voodoo Beer", another specialty brewed in a local brewery.

On Fat Tuesday itself, I joined the hundreds of thousands of local people and visitors, to watch the processions wind their way through the streets of New Orleans. The processions are organized by groups called "Krewes", which each have mythological or historic names, such as Proteus, Endemion, or Bacchus. The one I liked best was Zulu, a parade organized by members of the city's black community, resplendent with its colorful ornate floats and costumes based on African themes.

Perhaps the most astonishing aspect of Zulu and other parades was the "throws". As the floats move slowly through the crowds, tradition has it that those on them should throw all kinds of trinketsinto the crowd — plastic necklaces, engraved plastic cups, plastic medallions (a coveted prize) and other souvenirs. Most parade-goers do all they can to catch these materially worthless items, and I found myself quickly caught up in the frenzy, scraping on the sidewalk among the surging spectators to proudly pick up my plastic prize. In the heat of the moment, it's hard not to be caught up in the madness of this ritual, in spite of the worthlessness of the prizes!

Traditionally, people in New Orleans use the "throw cups" they pick up, and decorate their cars or homes with the other souvenirs they take home.

As a Yankee spending my first Mardi Gras in New Orleans, however, I made some mistakes in planning my time. There is so much going on at Carnival time, that you can't see everything, and I was disappointed not to see more of the city's famous Dixieland jazz bands parading through the streets, but obviously I was often in the wrong place at the wrong time.

After a year, I know that I still have a lot to learn about the customs, cultures and traditions of Mardi Gras in New Orleans. This year, I'll try and restrain myself during the throws, so that I won't come home with a bagful of plastic objects that I simply have to recycle. I'll let someone else have that pleasure!

7.COLLEGE SPORT - USA

If American athletes so often take the greatest number of medals, if American scientists and thinkers win so many Nobel prizes and other awards, and American businesses dominate the world, it is largely down to one word: competition.

If American athletes so often take the greatest number of medals, if American scientists and thinkers win so many Nobel prizes and other awards, and American businesses dominate the world, it is largely down to one word: competition.

Since the days of the pioneers, competition has been at the heart of the American way of life; and in today's USA, there are probably few areas where the competitive spirit is stronger than in the world of colleges and universities.

Rivalry between institutions is intense, and nowhere is this more true than on the sports field. Successful sports teams can be enormous assets to a college's reputation and public image, which explains why many go to incredible lengths to attract and recruit top high-school athletes.

There is a growing feeling, however, that in many cases they go too far. Recent media reports have focused on the extremely high drop-out rate among college sports scholars. While some abandon their education to take up lucrative professional contracts, most leave college with no degree, and no hope of entering the elite world of professional sport either. Pressured to achieve results in their sport, many have had no option but to put academic study on the back burner.

Their situation was recently highlighted by Rep. Ron Wilson, a Texas Democrat, who claims that colleges and universities are cheating many student athletes of a proper education.

"They entice them in with all kinds of promises of fame and fortune, they get them at university, and then only one out of ten of them graduates," he said. "The system doesn't really care about them."

One thing the system does care about, on the other hand, is money. College sport is big money in the USA, and the prestige attached to high performance athletes, and the colleges they represent, is enormous. NCAA (National College Athletic Association) rules state clearly that all college athletes must be amateurs, yet college sport is a multi-billion dollar business. Though it is registered as a tax-exemptcharity, the NCAA itself had a budget of 5.64 billion dollars in 2007.

One major source of income for the NCAA is a $6 billion college basketball contract with CBS television, an 11-year deal signed in 1999.

This and other expensive contracts have drawn a lot of criticism. Faculty members in many colleges have complained of the enormous sums of money spent on extensive high-quality sports facilities; and many students are increasingly bitter about the favors bestowed upon college sports champions.

Though it concerned a high school, not a university, the notorious 1999 massacre at Columbine High School was all about sport. One of the reasons that led Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold to go on their killing spree was their resentment at the privileges and status enjoyed by the "jocks", the heroes of the school's sports teams. Had they waited a year or two, Harris and Klebold might have emptied their guns on a university campus, not in a high school.

The arguments about the role and status of college athletes is one that preoccupies many students, athletes or not. It only takes a few minutes' searching on the Internet to turn up sites and discussion groups on the subject. The biggest issue right now seems to be the question of whether college athletes should be paid, like professionals.

NCAA rules are quite clear on this point. Apart from their sports scholarships, college athletes are not allowed to "receive any salary, incentive payment, award, gratuity, educational expenses or expense allowances" nor "use athletics skills for pay in any form". In reality, the situation is often very different, with many high-performance college athletes receiving undeclared benefits including free prestige cars (such as a BMW) and free housing.

Judging by comments on Internet forums, most college athletes think they deserve to be paid. Robert Krot, a basketball scholar, wrote: "I play college basketball, and I barely have time to do anything. There is no way I could hold a job. I don't come from a wealthy background, so I have to make do with what I have. College athletes should be paid."

But another writer, called Joss, disagrees; "The value of money is far greater than you think, it can mess up your mind. I know, because I play basketball; but you know, what I am also trying to become is a microbiologist, because I know I am not guaranteed to be drafted into the NBA."

If, in the years to come, college athletes do get the right to benefit from professional sponsorship, few people will be terribly surprised. Corporate sponsorship of university laboratories has helped the USA become world leader in scientific research. Corporate sponsorship of college sport is just another step in the same direction..... or at least, that is what some people say.

8.RODEO - The sport of the west

Rodeo is to America what bull-fighting is to Spain or horse-racing is to Britain: the nation's most popular animal sport, and a very popular sport at that. Paul Denman recently spent a day at the Deschutes County Fair, in Redmond Oregon, and joined hundreds of Oregonians to watch the highlight of the fair, the annual Deschutes Rodeo.

Bull riding - a uniquely Wild-West sport.

Bull riding - a uniquely Wild-West sport.

At 1 p.m. the air is still, heavy with a confusion of smells that drifts among the stalls and the barbeques, the animal enclosures and the ice-cream vendors. In the hot midday sun, the fair throngs with visitors, but there's little shade to sit in, just narrow strips of shadow alongside the buildings and the tents. All around, the music is playing while kids run riot and and stall-holders beckon passing visitors with their colorful displays.

Then, as the time moves towards 2.30, there is a new sense of excitement in the air: people are no longer moving round randomly, but heading in the same direction, towards the dusty arena to the south of the showground. It's almost time for the rodeo!

Here at last there is shade for everyone: the grandstand, with its tiered seating, rapidly fills up, as thousands of fair-goers pile in, eager for a good view of the excitement that is soon to begin.

Then, as the time moves towards 2.30, there is a new sense of excitement in the air: people are no longer moving round randomly, but heading in the same direction, towards the dusty arena to the south of the showground. It's almost time for the rodeo!

Here at last there is shade for everyone: the grandstand, with its tiered seating, rapidly fills up, as thousands of fair-goers pile in, eager for a good view of the excitement that is soon to begin.

Microlight kids on minuscule (matching) ponies

Microlight kids on minuscule (matching) ponies

For some people it has already begun. Microlight kids on minuscule ponies are cavorting round the empty arena, while a handful of cowboys, astride impeccably trained horses, walk or trot sedately round the ring. Suddenly a little blonde girl, hardly four feet tall, careers into view, riding bareback at the speed of light on bright white pony. No-one pays much attention. The folk in the stands are too busy talking about horses and rodeo-riders, discussing the last rodeo, predicting the winners of the next. Somehow, as someone who has not been brought up in the company of horses, I feel slightly out of place, as if everyone here except me knows everything about what is going on.

I had been to a couple of rodeos before, including the biggest of them all, the Calgary Stampede; but the other rodeos I had been to were put on for the tourists. Not this one; in central Oregon, there are few tourists. Rodeos here are for the locals, people who know them and understand them; most of the folk round me are from Redmond, or Prineville or Madras or Bend, certainly not from Europe!

Then action: suddenly the gates at the end of the arena burst open, and a posse of flag-carrying girls erupts into view, circling the arena in formation on shining dark ponies. Dressed in patriotic red white and blue, courtesy of Pepsi-Cola, the girls come to a stop in the middle of the ring, as the crowd rise to their feet, the men take off their stetson hats, and everyone joins in the singing of God Bless America. The rodeo has begun!

The rodeo has begun! For the next couple of hours, spectators watch with excitement as local heroes perform feats of dexterity on the backs of bucking animals! While some show their skills at calf roping — catching a running calf with a lasso and tying it up in just a few seconds — others demonstrate their daredevil skills by riding untamed broncos or bounding round on the backs of enormous raging bulls. As intrepid riders master or fall off their wild mounts, the crowd cheer wildly or aah in apprehension, then burst into laughter as the obligatory clown, the matador of the rodeo, distracts the attention of the raging animals while mounted cowboys round them up, calm them down, and coax them away into the pens from which they originally emerged, their day's work over.

I had been to a couple of rodeos before, including the biggest of them all, the Calgary Stampede; but the other rodeos I had been to were put on for the tourists. Not this one; in central Oregon, there are few tourists. Rodeos here are for the locals, people who know them and understand them; most of the folk round me are from Redmond, or Prineville or Madras or Bend, certainly not from Europe!

Then action: suddenly the gates at the end of the arena burst open, and a posse of flag-carrying girls erupts into view, circling the arena in formation on shining dark ponies. Dressed in patriotic red white and blue, courtesy of Pepsi-Cola, the girls come to a stop in the middle of the ring, as the crowd rise to their feet, the men take off their stetson hats, and everyone joins in the singing of God Bless America. The rodeo has begun!

The rodeo has begun! For the next couple of hours, spectators watch with excitement as local heroes perform feats of dexterity on the backs of bucking animals! While some show their skills at calf roping — catching a running calf with a lasso and tying it up in just a few seconds — others demonstrate their daredevil skills by riding untamed broncos or bounding round on the backs of enormous raging bulls. As intrepid riders master or fall off their wild mounts, the crowd cheer wildly or aah in apprehension, then burst into laughter as the obligatory clown, the matador of the rodeo, distracts the attention of the raging animals while mounted cowboys round them up, calm them down, and coax them away into the pens from which they originally emerged, their day's work over.

Every rodeo has its rodeo queen

Every rodeo has its rodeo queen

Katie Sharpe, 21, the local Rodeo Queen, does a lap of honour, then participates in the ladies' events; but in this macho part of the world, the ladies do not get to pitthemselves against untamed bulls and broncs! That's men's stuff! Katie and the other young ladies show their skills at "barrel racing", hurling their horses at breakneck speed round an triangular shaped race-course, marked out with barrels, in the middle of the arena. It's not as dramatic as bull-riding, but it's exciting, and the crowd roar their approval.

As the sun falls lower in the sky and the shadows begin to lengthen, the final rounds of calf-roping and saddle-bronc riding bring another half hour of thrills and spills before the commentator finally announces that the Rodeo is drawing to an end. The last prizes are handed out, the last riders leave the arena, and the show is over. As the spectators pick up their belongings and move slowly towards the exits, the kids on their ponies come back again for another few minutes as imaginary champions, tomorrow's local heroes in the arena of the stars. Here, it seems, if rodeo does not flow in the blood, at least it's all in the family.

As the sun falls lower in the sky and the shadows begin to lengthen, the final rounds of calf-roping and saddle-bronc riding bring another half hour of thrills and spills before the commentator finally announces that the Rodeo is drawing to an end. The last prizes are handed out, the last riders leave the arena, and the show is over. As the spectators pick up their belongings and move slowly towards the exits, the kids on their ponies come back again for another few minutes as imaginary champions, tomorrow's local heroes in the arena of the stars. Here, it seems, if rodeo does not flow in the blood, at least it's all in the family.

9.The Yukon Quest

A thousand-mile race that's said to be the toughest race in the world

Crossing Alaska.

Crossing Alaska.

Imagine mushing along broken snowy trails behind some of the toughest, sure-footed little athletes in the world; the only sounds to be heard are those of crunching snow, the hiss of the sled's runners, and the puffing of the team of dogs out front. This is life on the Yukon Quest, a ten-to-fourteen day dog-sled race across one of the coldest parts of the world - the northern parts of North America.

As the teams battle across the frozen wastes, temperatures can vary from freezing on the warmest of days, down to -62°C if cold weather really sets in. Hard packed snow, rough gravel, frozen rivers and mountain terrain can make the trail fast at times, or else slow to a crawl.

There are other long-distance sled-dog races; but none quite like the Yukon Quest, which follows a trail across some of the most sparsely populated and undeveloped terrain in North America. Named after the Yukon river, the Quest takes teams from Fairbanks, Alaska, to Whitehorse, Canada in even-numbered years, and the other way round over the same route in odd-numbered years - a trail once followed by miners and trappers on their way to and from the icy North.

Teams come from all over North America to take part in this the hardest of sled-dog races. Depending on the year, up to 35 teams take part - each team being composed of a "musher" and up to 14 dogs.

Training for the race is long and hard, and the teams that start out on the Quest in mid February have been training since August. Dogs and men have to be in tip-top condition, to confront the 1000 miles of the race, which take them almost up to the Arctic Circle.

Running 1000 miles - about the same as running 3 marathons a day for 11 days in a row - would be impossible for humans; but this is the challenge that faces the dogs. In order to cover up to 100 miles some days, much of the time in darkness, the teams generally alternate six to eight hour periods of running and resting - mushers sleeping on their sleds, the dogs in the snow.

Since the race was first run in 1984, teams and equipment have improved; in 1984, the winning team completed the race in just 12 days. For the next twenty-five years, winning times were mostly ten or eleven days, depending on the weather conditions. But then, in 2009 Canadian musher Sebastian Schnuelle first finished in less than 10 days; then five years later American musher Allen Moore had a winning time of under 8 days and 15 hours.

Though physical fitness is of paramount importance both for dogs and mushers, a musher needs to know his dogs perfectly before taking them out on such a gruelling test of endurance. Performance, nutritional needs, stress symptoms and other aspects of the dogs' physical and mental conditions need to be precisely assessed.

Starting with a maximum of 14 dogs, each musher has to reach the end with no fewer than 6. Vets are on hand at check-points along the route to keep detailed track of each animal's condition; but between check points, it's the musher himself who has the job of making sure that his animals remain in good form. Blood tests, urine samples, measurements of weight gain or loss and body temperature are all carefully examined, to make sure that each animal remains fit and healthy. Dogs are constantly checked for dehydration and fatigue - and if there is any doubt about an animal's ability to continue the race or not, it is dropped off at the first available opportunity.

The interdependence between a musher and his animals is total - the dogs relying totally on their musher to take care of them, and the musher depending totally on the dogs to get the sled across the snowy miles, and ultimately to the distant destination.

The Yukon Quest is probably not the only claimant to the title of "the toughest race in the world". There can be few others however - if any at all - that can have such a valid claim to this superlative.

As the teams battle across the frozen wastes, temperatures can vary from freezing on the warmest of days, down to -62°C if cold weather really sets in. Hard packed snow, rough gravel, frozen rivers and mountain terrain can make the trail fast at times, or else slow to a crawl.

There are other long-distance sled-dog races; but none quite like the Yukon Quest, which follows a trail across some of the most sparsely populated and undeveloped terrain in North America. Named after the Yukon river, the Quest takes teams from Fairbanks, Alaska, to Whitehorse, Canada in even-numbered years, and the other way round over the same route in odd-numbered years - a trail once followed by miners and trappers on their way to and from the icy North.

Teams come from all over North America to take part in this the hardest of sled-dog races. Depending on the year, up to 35 teams take part - each team being composed of a "musher" and up to 14 dogs.

Training for the race is long and hard, and the teams that start out on the Quest in mid February have been training since August. Dogs and men have to be in tip-top condition, to confront the 1000 miles of the race, which take them almost up to the Arctic Circle.

Running 1000 miles - about the same as running 3 marathons a day for 11 days in a row - would be impossible for humans; but this is the challenge that faces the dogs. In order to cover up to 100 miles some days, much of the time in darkness, the teams generally alternate six to eight hour periods of running and resting - mushers sleeping on their sleds, the dogs in the snow.

Since the race was first run in 1984, teams and equipment have improved; in 1984, the winning team completed the race in just 12 days. For the next twenty-five years, winning times were mostly ten or eleven days, depending on the weather conditions. But then, in 2009 Canadian musher Sebastian Schnuelle first finished in less than 10 days; then five years later American musher Allen Moore had a winning time of under 8 days and 15 hours.

Though physical fitness is of paramount importance both for dogs and mushers, a musher needs to know his dogs perfectly before taking them out on such a gruelling test of endurance. Performance, nutritional needs, stress symptoms and other aspects of the dogs' physical and mental conditions need to be precisely assessed.

Starting with a maximum of 14 dogs, each musher has to reach the end with no fewer than 6. Vets are on hand at check-points along the route to keep detailed track of each animal's condition; but between check points, it's the musher himself who has the job of making sure that his animals remain in good form. Blood tests, urine samples, measurements of weight gain or loss and body temperature are all carefully examined, to make sure that each animal remains fit and healthy. Dogs are constantly checked for dehydration and fatigue - and if there is any doubt about an animal's ability to continue the race or not, it is dropped off at the first available opportunity.

The interdependence between a musher and his animals is total - the dogs relying totally on their musher to take care of them, and the musher depending totally on the dogs to get the sled across the snowy miles, and ultimately to the distant destination.

The Yukon Quest is probably not the only claimant to the title of "the toughest race in the world". There can be few others however - if any at all - that can have such a valid claim to this superlative.

10.Highway 66 revisited -

A trip along America's historic Route 66

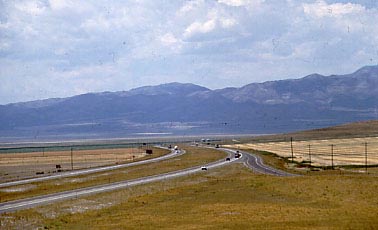

The car is the cornerstone of modern American life; yet cars need roads, and so the road too is a cornerstone. But while cars have regularly been raised to the status of cult objects in song, poetry and film, roads have tended to keep a more prosaic image. Occasionally there have been exceptions: Bob Dylan named one of his most famous albums for a road — Highway 61 Revisited — and Jack Kerouac gave pride of place to a highway in his classic novel On the Road. Yet in the culture and history of twentieth century America, one highway stands out from the rest; and although it no longer exists, except in small sections here and there, "Route 66" is without the shadow of a doubt the most famous highway in the United States of America.

The car is the cornerstone of modern American life; yet cars need roads, and so the road too is a cornerstone. But while cars have regularly been raised to the status of cult objects in song, poetry and film, roads have tended to keep a more prosaic image. Occasionally there have been exceptions: Bob Dylan named one of his most famous albums for a road — Highway 61 Revisited — and Jack Kerouac gave pride of place to a highway in his classic novel On the Road. Yet in the culture and history of twentieth century America, one highway stands out from the rest; and although it no longer exists, except in small sections here and there, "Route 66" is without the shadow of a doubt the most famous highway in the United States of America.Steinbeck, who knew it well, called it "the Mother Road". It was the road taken by the Joad family in the Grapes of Wrath; for them, as for hundreds of thousands of real-life dustbowl refugees, Route 66 was the road that led from the hell of dusty Oklahoma to the paradise of California, where the peach trees and vines were always laden with succulent, luxurious fruit, just waiting to be picked. At least, that was the popular myth.

Those who like listening to American music may have heard the song Route 66, originally recorded by Nat King Cole, and since then re-recorded dozens of times by a bevy of artists including The Rolling Stones, Chuck Berry and Depeche Mode: the words of the song detail the full itinerary of the US Highway 66, which "windsfrom Chicago to L.A., more than two thousand miles all the way."

Those who like listening to American music may have heard the song Route 66, originally recorded by Nat King Cole, and since then re-recorded dozens of times by a bevy of artists including The Rolling Stones, Chuck Berry and Depeche Mode: the words of the song detail the full itinerary of the US Highway 66, which "windsfrom Chicago to L.A., more than two thousand miles all the way."Today, little is left of the most famous of all America's highways. Here and there, in Illinois or in Kentucky, sections of the famous road still display the sign 66; but 66, where it does survive, is no longer a key element in a continental highway system as it once was — just a local highway linking neighboring towns. The development of America's transcontinental system of divided-highway "interstates" during the 1950's and 1960's meant that the Mother Road rapidly became obsolete, and in 1977, fifty-one years after it was created, U.S. 66 officially ceased to exist. By then, almost everyone wanting to "motor west" was using the main east-west interstates, I-40, I-60 or I-80.

It was in 1926, the year in which Henry Ford launched the Model-T and put the automobile in reach of the ordinary American, that officials decided that the U.S.A. should have a federal road network. In Oklahoma, a businessman called Cyrus Avery, who quickly saw the advantage of bringing a transcontinental highway through his state, immediately started lobbying officials to create a single highway running all the way from the Great Lakes to the Pacific, and passing through Oklahoma; it would be the longest federal highway in the U.S.A..

Avery's plan was accepted, and the number 66 was chosen — a nice memorable number. Avery and others wanted to attract business to the road and all kinds of promotional activities were organized, including an amazing trans-America running race from L.A. to New York, via Chicago; of the 275 runners who began the race, 55 actually ran the whole way.

When it opened, only 800 of the 2,400 miles were paved; the rest were just gravel or earth, and it was not until 1937 that the whole route was paved. Even then, however, it was a hard journey. In winter time most of the route ran through bitterly cold regions; and in summer, the sections through new Mexico, Arizona and the California desert were extremely hot. In those days, cars regularly overheated, passengers needed regular sustenance, and the service stations, restaurants cafés and motels that appeared at short intervals all along the route did a good trade.

When, bit by bit, 4-lane interstates replaced the old highway, business collapsed very rapidly for many of those who had helped so many travelers on their way. In agricultural regions, towns and communities could survive without the road, but in the sparsely-populated desert areas, many small communities just disappeared. Today, for instance, nothing but a solitary palm tree and a wooden signboard marks the site of the one-time Bagdad, California. Elsewhere, empty roofless stone buildings that were once garages or hotels stand abandoned to the wind and the elements. On some sections of the old road, cars pass by at the rate of one an hour or less

When, bit by bit, 4-lane interstates replaced the old highway, business collapsed very rapidly for many of those who had helped so many travelers on their way. In agricultural regions, towns and communities could survive without the road, but in the sparsely-populated desert areas, many small communities just disappeared. Today, for instance, nothing but a solitary palm tree and a wooden signboard marks the site of the one-time Bagdad, California. Elsewhere, empty roofless stone buildings that were once garages or hotels stand abandoned to the wind and the elements. On some sections of the old road, cars pass by at the rate of one an hour or lessIn recent years, there may be a few more; the story of Route 66 is coming to be recognized as history, and a few adventurous travellers are driving along sections of it, reliving the spirit of the past. It's a road for people with time to spare, and a taste for a long journey. In 2011, Scottish TV presenter Billy Connolly spent weeks travelling the route from end to end, for a four-part TV documentary; yet few, very few, travel the whole road, or what is left of it. Even in the latest air-conditioned Cadillac, Route 66 remains what Woody Guthrie called "a mighty hard road."

11.The Mighty Mississippi

For three or four months in the year, you can walk across long parts of the Mississippi; in fact, you can walk along it too, or drive horses across it.

For three or four months in the year, you can walk across long parts of the Mississippi; in fact, you can walk along it too, or drive horses across it.

Motionless in the winter's icy grip, the surface of North America's most famous river lies hidden for weeks on end beneath a cold white blanket of snow.

But below the surface the water flows on in silence, moving relentlessly through the frozen heartland of North America, towards warmer and more colorful lands.

"Old Man River" is no more than a child in the state of Minnesota, where he is born among the lakes and the forests not far from the Canadian border. If he had chosen to move north or west, he would have finished up in the Atlantic Ocean, part of America's other great river, the Saint Lawrence. But the child that is to turn into Old Man River moves south.

He makes his way towards the Gulf of Mexico. It's a distance of 1,500 miles as the crow flies, but more like 2,500 miles along the meandering course that he chooses. It will be several weeks before the waters that rise in Minnesota eventually flow out past the ocean-going ships tied up at New Orleans, and mingle with the salt of the sea.

Of course, Old Man River has been making more or less the same southward journey for thousands of years: long before anyone thought of calling him "Old Man River", he had no name. It was the Algonquin Indians who gave him the name "Mississippi"; in their language, the name meant Great River. The name has stuck.

The first European to set eyes on the great river was a Spanish explorer, called De Soto, who came across the mouth of the river in 1541; yet it was not until over a century later that the Mississippi river began to take a significant place in the history of North America. In 1682 a French explorer called La Salle set off from the Great Lakes region, followed the Ohio river, and eventually reached the coast. Having established an alternate route from the Great Lakes to the sea, La Salle claimed the whole of the Mississippi basin for the French king Louis XIV, and called it Louisiana in his honour.

For almost a century, the Mississippi valley was French territory, sandwiched between the British colonies to the east, and "New Spain" and the unexplored prairies to the west. Little French colonies appeared along the banks of the river, but in most cases their names are the only things about them that remain from their early days: St. Cloud, La Crosse, Prairie du Chien, St. Louis, and many more. It is only at the mouth of the river, round New Orleans and Baton Rouge, that the river's French past still lives on, to a limited degree. New Orleans' "Mardi Gras" celebrations are among the most colorful in the United States, a hybrid fusion of old French tradition and Afro-American celebration.

In 1783, the land to the east of the Mississippi became the western frontier of the newly born United States of America. As for the much larger area of land to the west, it was sold to the United States by Napoleon in 1803, for the sum of $11.5 million, in the historic "Louisiana Purchase".

Nevertheless, even before the Louisiana Purchase, American settlers had begun pushing across the river, searching for places to settle in the virgin territory beyond. And as the great wide valley filled up with more and more farms, towns and markets, so the importance of the river grew.

During the cotton boom of the early nineteenth century, the river and its tributaries allowed plantation owners to get their produce easily down to New Orleans, where it could be exported to markets all over the world, and particularly to the textile mills of Lancashire, England.

DANGEROUS MISSISSIPPI

The Mississippi drains a basin that covers 41% of the continental United States (excluding Alaska), stretching from Montana in the West to New York in the East. It is the third largest river basin in the world, after the Nile and the Congo.

With such a large continental basin, the Mississippi is a river whose flow can be erratic; at the mouth of the river, the average flow is about 13,000 cubic metres per second. However, experts estimate that the maximum flow could reach 85,000 cubic metres per second under exceptional circumstances; currently, river engineers are working on "Project Flood", to make sure that outlets into the Gulf of Mexico can cope with a flow of this magnitude.

With such a large continental basin, the Mississippi is a river whose flow can be erratic; at the mouth of the river, the average flow is about 13,000 cubic metres per second. However, experts estimate that the maximum flow could reach 85,000 cubic metres per second under exceptional circumstances; currently, river engineers are working on "Project Flood", to make sure that outlets into the Gulf of Mexico can cope with a flow of this magnitude.The risks of flooding have been clearly understood from the day people first began to settle beside the river. Many of the towns and settlements beside the river are situated on "bluffs", others are protected. It was French engineers who first began protecting the land beside the river by building up long dikes, which they called "levees", a French word meaning "raised banks"; today, thousands of square miles of farmland and dozens of towns and are protected by levees.

Most of the time, the levees do their job; but not always. In 1993, hundreds of square miles of land were flooded, and millions of dollars' worth of damage done when the mighty river became too mighty, and broke through the defenses.

12.Bodie - where the West was Wildest

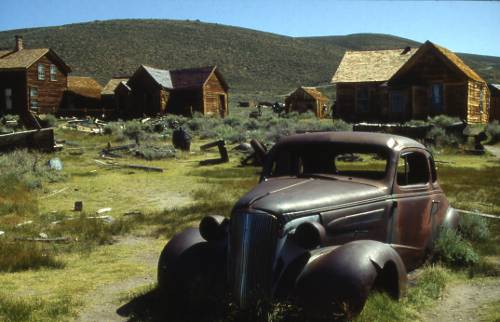

The spirit of the "Wild West" has been one of the defining themes of American culture - literature, film and art - for the last 150 years. But the great age of the Wild West was actually rather short. It began around 1850, with the opening up of the American west, but by 1900 it was over. Towns appeared one year, and disappeared a few years later. One of the finest examples is the California "ghost town" of Bodie, which was once said to be the wildest town in the Wild West.

Once this was one of the wildest places in the Wild West.

Once this was one of the wildest places in the Wild West.

Today the second biggest city in California is San Francisco. Once it was Bodie.

"Bodie?", you say. "Where's that?"

Good question. But in 1880 in America, reactions would probably have been very different. Then, Bodie, with its population of over 10,000, was one of the most infamous places in the whole U.S.A., reputed as the worst, most violent and most lawless town in the Wild West. Many historians have quoted a letter from a young girl whose parents decided to go and live and work in Bodie; even this 12-year old knew of Bodie well by reputation, and in her diary she wrote: "Goodbye God! I'm going to Bodie". Bodie was "hell on earth".

In 1859, a gold prospector named William Body (pronounced like "roadie") discovered gold-bearing rock in a desolate part of the California desert. Claiming the stake in his name, he set up a base cabin there with two friends.

Since it was the start of winter, Body and one of his companions then went off to buy stores from the nearest shop..... about a hundred miles away. By the time they started back however, the temperature and the winter snows had begun to fall; and as the snow got deeper and deeper, the journey got harder and harder. Though the men were tough and knew how to survive under most circumstances, they had not reckoned with the terrible cold in the high California desert, situated at an altitude of over 2,500 metres. A few hundred metres from their cabin, Body collapsed. His friend struggled on to get help, but by the time it came, the snow had covered up his tracks completely. William Body's body was not found until the following spring.

Thus Body never extracted a single ounce of gold from his claim; but since it was his claim, the mining camp, then town, that grew up on the spot got named after him.

According to legend, the town's name changed from Body to Bodie because a sign-writer could not spell correctly. In actual fact, the change was deliberate, the townspeople did not want the name to be mis-pronounced. "Body" (rhyming with "shoddy") and implying a dead corpse, sounded rather macabre!

At first the town grew slowly, as there was more gold to be found in some other towns in the region, than near Bodie; besides, Bodie was such a desolate spot! It was not until some very rich veins of gold were discovered in 1876 that the Bodie gold rush really began.

Like most gold rush towns, Bodie grew very fast, then shrank again almost as fast, as the gold ran out. Maximum size was reached in 1880, when the town boasted 65 saloon bars and its own daily newspaper, in which its violence and lawlessness were reported in fine detail. On 5th September 1880, for example, the Bodie Standard reported three shootings, plus two hold-ups of stage coaches in one day!

By 1885, the town's population had dropped to a couple of thousand, many of the miners having gone off to seek better fortunes elsewhere; many of the town's wooden buildings had been burnt down. Fire, indeed, was a permanent risk in Bodie's dry climate, and the town was actually destroyed several times in its history, the last time in 1932.

It survived until then as a small town, providing services to the local area; but the 1932 fire signed the town's death warrant. Many of the facilities were destroyed, as were the homes of many of the surviving residents. After the fire, there was no reason for people to go on living in Bodie.

The man who did most for Bodie was Jim Cain, who opened the town's first bank in 1880. He was also one of the most successful of Bodie's miners, and as the town declined, he bought most of the buildings that no-one else wanted — including the principal mine.

After Bodie was abandoned by its last inhabitants during the Depression of the 1930's, Cain saved the town from total destruction. A watchman was installed at the mine, and his job was to make sure that no-one came and dismantled the remaining wooden buildings (as happened

to so many other ghost towns).